UN report sees progress, areas of concern, in sustainable development goals report

Reading Time: 4 minutesMalaysia, Thailand, and Singapore have made significant advances in economic development and infrastructure, efforts on sustainability and equality targets remain uneven, the United Nations’ ESCAP 2025 SDG (sustainable development goals) Progress Report found.

Thailand leads the trio in overall SDG achievement and ranks first in ASEAN, which is comprised of the three aforementioned countries as well as Indonesia, Vietnam, Laos, Brunei, Myanmar, the Philippines and Cambodia.

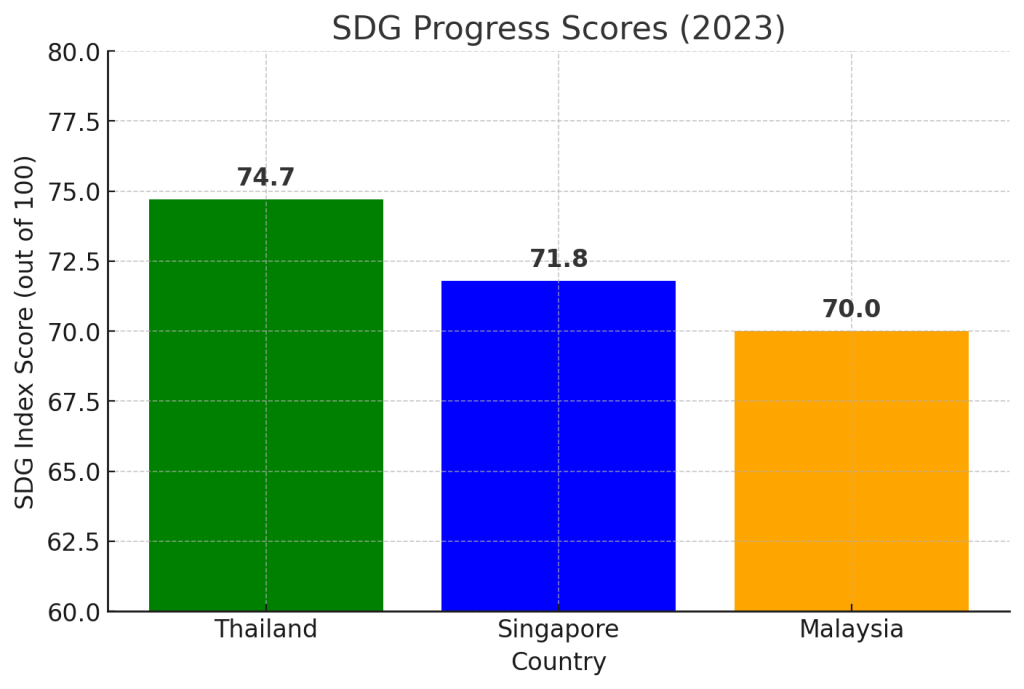

In 2023, Thailand scored 74.7 out of 100 on the global SDG Index, placing it 43rd worldwide. Singapore followed with a score of 71.8, ranking 64th globally, while Malaysia scored around 70 and ranked 78th. This means Thailand has maintained the top SDG performance in Southeast Asia (SEA) for five consecutive years, according to Economic and Social Commission for Asia and the Pacific (ESCAP).

The report warns that progress across SEA has been slow, even among leading nations. Environmental sustainability remains challenging, particularly regarding consumption, climate action and sustainable urbanisation. Greenhouse gas emissions continue to rise, and Thailand, Malaysia, and Singapore still subsidise fossil fuels despite their stated climate commitments.

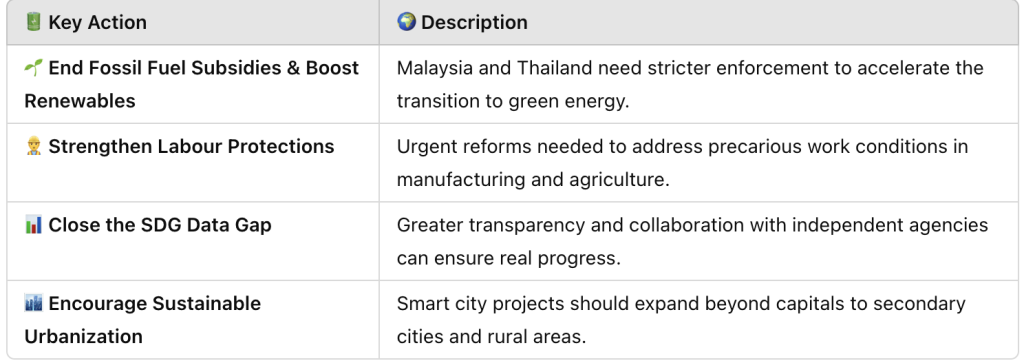

Malaysia’s fuel subsidies have been particularly high, exceeding MYR 5bn (USD 1.23bn) in a single month in 2022. Thailand has also maintained price caps on diesel, while Singapore has taken a different approach by taxing fuel instead of subsidising it. These policy differences impact SDG performance, as Malaysia and Thailand’s subsidies discourage investment in renewable energy.

All three countries have made substantial progress in poverty eradication and education, with near-universal access to basic services. However, none are on track to achieve all 17 SDGs by 2030.

Singapore and Malaysia have some of the highest per capita carbon footprints in SEA, at around seven to eight tonnes of carbon dioxide per capita annually, compared to Thailand’s around four tonnes. Singapore’s status as a high-income urban economy and Malaysia’s reliance on fossil fuels contribute to these higher emissions. While all three countries have announced plans to increase renewable energy use, none are currently on track to meet their Paris Agreement targets.

Urban sustainability is another area where progress has been mixed. Singapore has invested heavily in public transport and housing, virtually eliminating slum conditions. Malaysia has also reduced informal housing, though Kuala Lumpur still faces congestion issues. Thailand has made strides in expanding public transport and green spaces, but urban poverty remains a challenge. In Bangkok’s informal settlements, surveys have highlighted poor sewage systems and limited access to clean water. Sustainable urbanisation policies must expand beyond capital cities to secondary urban centres and rural areas, ESCAP adds.

Economic growth has been strong in all three countries, but concerns remain about labour rights and income inequality. The ESCAP report warns that progress on working conditions is too slow across SEA. National labour laws restrict freedom of association and collective bargaining in Malaysia and Thailand, while migrant workers in Singapore have limited protections. These issues are reflected in global rankings, where all three countries receive low scores on compliance with labour rights. Strengthening workplace protections and expanding social safety nets will be critical for achieving progress on employment-related SDGs.

Economic inequality remains a persistent issue despite overall economic growth. Malaysia has one of the highest levels of income inequality in Asia, with a Gini coefficient of around 0.39 in recent years. The World Bank has noted that Malaysia’s level of inequality is unusually high for a country approaching high-income status. Thailand has historically had one of the most unequal income distributions in the region, though it has made modest improvements. Singapore, while virtually free of extreme poverty, has a high cost of living that exacerbates social inequality. In all three nations, the top 20% of households have a disproportionate share of income while lower-income groups struggle to keep up.

Data transparency remains a major obstacle to effective SDG tracking. Across the Asia-Pacific region, only 54% of SDG indicators have sufficient data points to measure progress accurately. While Singapore, Malaysia and Thailand have relatively strong data collection systems, gaps remain, particularly in disaggregated data by age, gender, and location. These gaps can obscure inequalities, making it harder to assess whether policies are benefiting all segments of the population. The ESCAP report calls for greater cooperation with independent agencies and civil society to improve SDG data collection.

Malaysia, Thailand, and Singapore each have strengths and weaknesses in SDG implementation: Singapore leads in infrastructure, digital innovation and economic efficiency but struggles with sustainability and social inequality; Thailand has made significant strides in poverty reduction, rural electrification, and community-based programs but still faces challenges in urban planning and environmental sustainability; meanwhile Malaysia has strong economic momentum but remains reliant on resource-intensive industries and has weak labour protections.

Thailand, Malaysia and Singapore are in a better position than many developing economies for infrastructure, technology and industrial capacity. However, policy contradictions, economic short-termism, and weak environmental enforcement continue to drag down SDG progress. Without stronger institutional oversight and genuine investment in sustainability, the region risks missing key 2030 targets: not due to a lack of capability but a lack of political will.

The report emphasises that while each country has made progress in some areas, urgent reforms are needed to achieve the SDGs by 2030. Environmental sustainability, labour rights, and economic equality remain the biggest hurdles. Without stronger commitments to these areas, the region risks falling further behind its targets, ESCAP concludes.