SEA turns to China as Western aid retreats – Lowy report

Western aid cuts and rising loans from China, the Asian Development Bank (ADB) and the World Bank are transforming development finance across Southeast Asia (SEA), a new Lowy Institute report finds.

ASEAN foreign aid increasingly regional loans

Western donors are retreating from SEA, while development finance from China is surging, according to the Lowy Institute’s 2025 Southeast Asia Aid Map.

According to the report, "contributions from other donors declined as a group, led by a steep 28% drop in funding from Germany, the largest bilateral European development partner in the region."

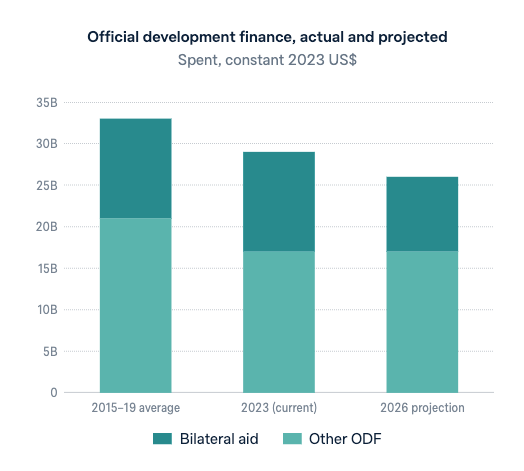

SEA received almost USD 29bn in official development finance (ODF) in 2023, the vast majority of which was loans, not grants, up from USD 26.5bn in the previous year, driven by an increase in non-concessional loans. "However, the region’s ODF remains well below pre-pandemic levels," the Australian think tank found.

Lowy wrote that "China ramped up disbursements by almost 50% compared to 2022, accelerating the implementation of major infrastructure projects such as the Jakarta-Bandung High-Speed Rail in Indonesia and the East Coast Rail Link in Malaysia. Multilateral development banks (MDBs) also increased their ODF disbursements.

"In 2023, China also finalised the revival of the Kyaukphyu Deep Sea Port project under the China-Myanmar Economic Corridor framework, resulting in a fourfold rise in the dollar value of new project commitments, from a low of USD 2.5bn in 2022 to almost USD 10bn in 2023.

Lowy Institute Indo-Pacific Development Centre Deputy Director Alexandre Dayant told CNBC that the report reflects “a contraction of aid and development finance provided by the West. And when we talk about the West, we mean the US, the UK… and also many other European countries."

Dayant added that China and "the West" have very different approaches to aid and development finance. The report said, "Beijing is recalibrating its approach, shifting towards fewer, smaller and more targeted infrastructure projects. In 2023, China financed just 17 projects worth USD 3.5bn, a 17% increase from 2022 but still far below the 67 projects and USD 5.2bn recorded in 2015."

Dayant said, “This is very needed in SEA, which faces a massive infrastructure gap. Think railways, energy, power plants. That’s where China spends.

"The US, UK and EU focused a lot on human development - programmes for education, health and social protection. Australia, for instance, has not cut its aid programme but focuses heavily on governance, making SEA public institutions stronger and more accountable. But China isn’t filling the gaps the West is leaving in education, health, and governance," Dayant added.

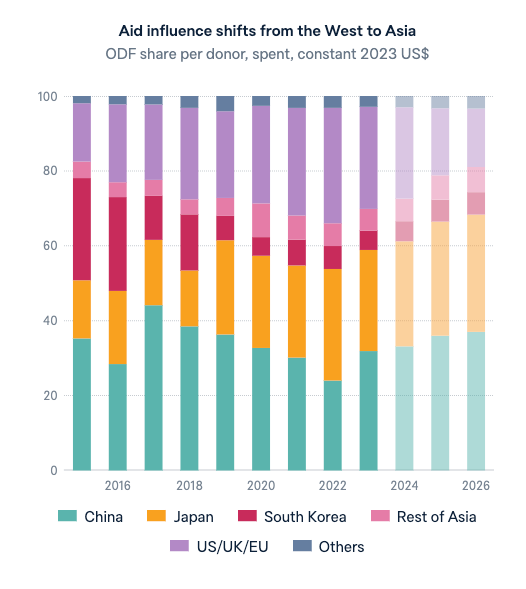

ODF from Asian donors is expected to remain broadly stable in the near term. Aid cuts by major Western donors will therefore see the centre of gravity in SEA’s development finance landscape drift towards Asian donors.

The Western retreat has come after several years of its donors increasing their relative importance in SEA, while China’s ODF fell. In future, Lowy said, development finance in SEA will be increasingly shaped by Tokyo, Seoul and Beijing, leaving the EU and the US with a diminished role. China could gain in importance, especially around the Mekong, and in Indonesia.

The main sectors of foreign investment in SEA in 2023 were transport and storage, government and civil society, banking and financial services, health and energy, which made up over two-thirds of the total.

Vietnam regional model for green loans

While countries including Cambodia and Laos remain reliant on grants from traditional donors, larger ASEAN economies are turning to loan packages for big-ticket projects in energy, transport and climate resilience.

ODF has decreased relative to Vietnam’s economy, down to 0.7% in 2023 from 3.9% in 2015. Lowy wrote. ODF to Vietnam is most commonly delivered through concessional loans, accounting for 46% of total ODF received, while 38% is delivered as non-concessional loans, and the remainder as grants.

Japan is Vietnam’s primary development partner, accounting for almost one-fifth of its total ODF received since 2015. The World Bank and South Korea comprise Vietnam’s second tier of partners, followed by the ADB and China, Lowy added.

Cambodia increasingly relies on loans

China, Japan, and the ADB have been Cambodia’s primary development partners, together accounting for almost 60% of its ODF since 2015.

A dramatic collapse in China’s spending in Cambodia in 2022 has been partially corrected by ongoing disbursements for large infrastructure projects, but 2023 levels were still lower than China’s average yearly spend from 2015-22. China accounted for only 28% of Cambodia’s ODF in 2023, down from 45% in 2021. A substantial 89% of China’s support to Cambodia has been delivered through loans, of which 59% have been concessional, Lowy noted.

Japan’s contribution has grown, and while still lower than China’s, it has not experienced the same volatility and is offered consistently as grants and concessional loans. Japan’s long-term focus on transport and storage has been maintained, with that sector now accounting for 38% of Japan’s total assistance to Cambodia since 2015, according to the report.

Thailand spends ODF on transport infrastructure

Thailand's ODF disbursements including grants, loans, and other forms of assistance experienced volatility from 2015 to 2023. After rising rapidly in 2016 and 2017, levels dropped again until a boom in 2021 as partners responded to the pandemic. However, 2023 ODF levels to Thailand were lower than in 2015.

ODF has fluctuated relative to Thailand’s economy but remains below 1% of GDP. SEA’s second-largest economy, Thailand’s ODF to GDP ratio is the third-lowest in the region. ODF is most often provided to Thailand through loans, with 47% non-concessional loans, 36% concessional loans and the rest grants.

Thailand’s primary development partners are China - responsible for more than one-third of Thailand’s ODF received from 2015-23 - the ADB, and Japan. While their relative weighting has shifted over time, those three partners have accounted for more than 80% of Thailand’s ODF.

"China’s support to Thailand peaked in 2017, coinciding with the height of the Belt and Road Initiative. The major sector of investment for China’s ODF is transport and storage, through a multi-billion-dollar loan for high-speed rail. There is a relatively even split in China’s ODF between concessional and non-concessional loans, with very limited use of grants.

"The US, South Korea, and Germany make up Thailand’s second tier of development partners, collectively contributing around 11% of ODF from 2015-23. Looking ahead, new commitments to Thailand have dropped dramatically from peaks in 2015 and 2019," Lowy commented.

Japan biggest backer of Myanmar

Japan is Myanmar’s primary development partner, accounting for almost one-quarter of its total ODF received since 2015, and higher in recent years, Lowy wrote. China, the US, the World Bank, and the ADB together comprise just under an additional third of Myanmar’s ODF over the data period.

Japan’s contribution has averaged around USD 620mn annually, with a major surge in 2020 for pandemic support. But in 2021, it dropped by almost two-thirds, and since the coup has hovered around USD 415mn per year. Japan’s support is provided entirely through official development assistance, increasingly via concessional loans rather than grants.

By contrast, most of China’s support, averaging USD 340mn per year, is delivered through non-concessional loans. China’s activities in Myanmar are difficult to assess because of a lack of transparency, meaning the Southeast Asia Aid Map may underestimate China’s engagement, Lowy underlined.

In absolute terms, Timor-Leste receives the least ODF in developing SEA. However, Timor-Leste receives the highest amount of ODF relative to the size of its economy, with ODF equivalent to 14% of GDP in 2023. Reflecting its low income level, 87% of ODF received by Timor-Leste is in the form of grants.

China backs Malaysia's megaproject

With a population of 5.9mn, Singapore’s per capita GDP of USD 84,734 is the highest in SEA, Lowy wrote, adding that its ODF programme is modest. From 2015-23, Singapore spent only USD 6.3mn in development finance in SEA.

Singapore also receives a small amount of development finance, totalling USD 7.2mn from 2015-23. Japan and the US were Singapore’s major source of ODF, responsible for over 88% of these disbursements. Other donors include the UK and the EU.

Malaysia’s primary development partner is China, accounting for 82% of ODF received from 2015-23. China’s assistance, totalling USD 9.5bn from 2015-23, is underpinned by one infrastructure megaproject, the multi-billion-dollar East Coast Rail Link, which has so far attracted USD 5.7bn in non-concessional loans.

South Korea was Malaysia’s top partner in 2015, but its support has since dwindled. South Korea’s decline from Malaysia’s top development partner appears largely due to a major contraction in non-concessional loans.

Korean ODF has targeted the energy and industry, mining and construction sectors, especially in the early years of the data period. By 2023, however, education, government and civil society and health sectors topped the list. Behind China and South Korea, Malaysia’s second tier of partners included Japan, Germany, the UK and the US.

ASEAN reaches donor crossroads

SEA is one of the most dynamic and fast‑growing regions in the world, both in terms of economic growth and population, Lowy summarised. However, SEA continues to face significant development challenges, including poverty, inequality, lack of access to education and healthcare, political instability and vulnerability to natural disasters.

Since the end of the Southeast Asia Aid Map reporting period in 2023, many major Western donors have chosen to step back from international development efforts, Lowy added.

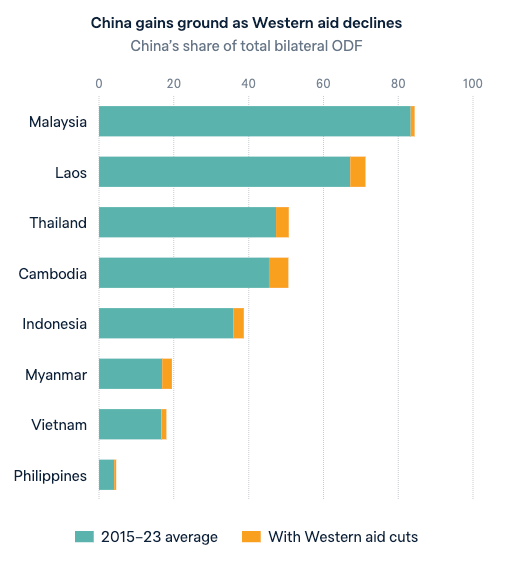

"In 2024, seven European governments (France, Germany, the Netherlands, Sweden, Finland, Austria and Italy) and the EU announced USD 17.2bn in ODA cuts to be implemented between 2025 and 2029. Even more notable have been the reductions by the US, with the Trump administration in early 2025 abruptly halting around USD 60bn - the majority of its overseas aid. The UK followed, announcing reductions in annual ODA of around USD 7.6bn. These cuts will hit Southeast Asia hard," Lowy wrote.

"Based on current budget documents, public announcements and calculations by other researchers, we estimate that total ODF to SEA could decline by 8%, or more than USD 2bn, falling to USD 26.5bn by 2026," the Australian think tank added.

According to Dayant, official development finance in SEA should be seen through two lenses. "First is the development lens: we want financing that strengthens public institutions, education, and health systems that can withstand future pandemics. Second is the geopolitical lens: how much aid translates into geopolitical advantage (where) middle powers are trying to compete with China in the Indo-Pacific.

"So what the Australian government should do is deepen collaboration with like-minded partners such as Japan and Korea, which are also active in the Pacific. Together, we should identify and fill the strategic gaps the US and the West are leaving.

"But it’s difficult to know what will happen. What we do know is that Western withdrawal will worsen the development divide in SEA, and this may threaten ASEAN unity," Dayant added.